Traceability rule changes looming with FSMA 204

With traceability rule changes looming, experts discuss proposed FSMA 204 and its effect on the produce industry.

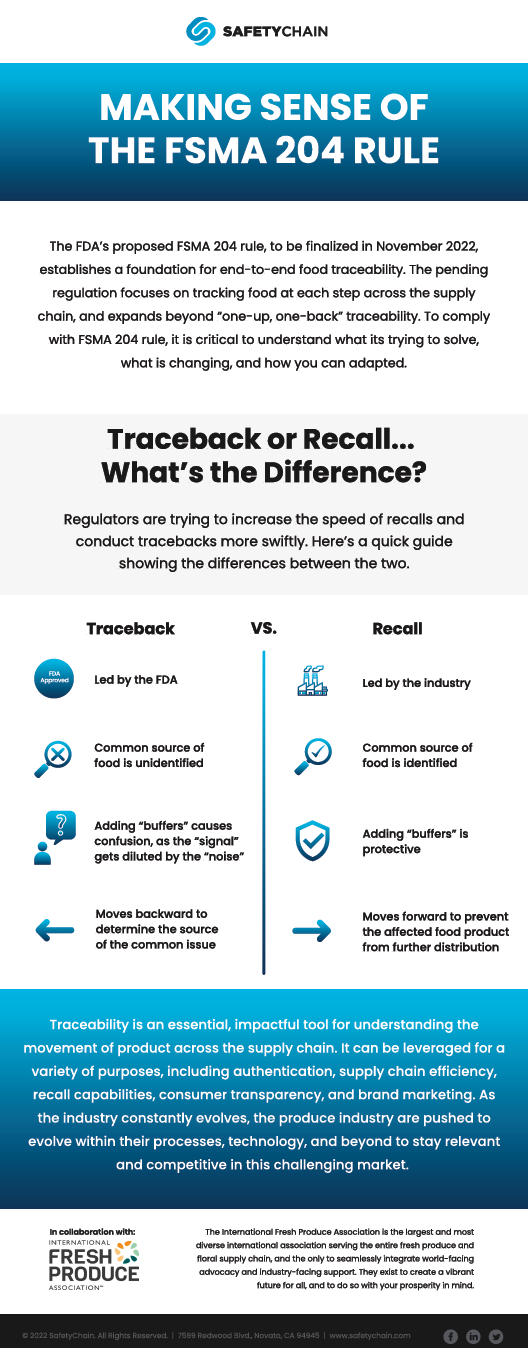

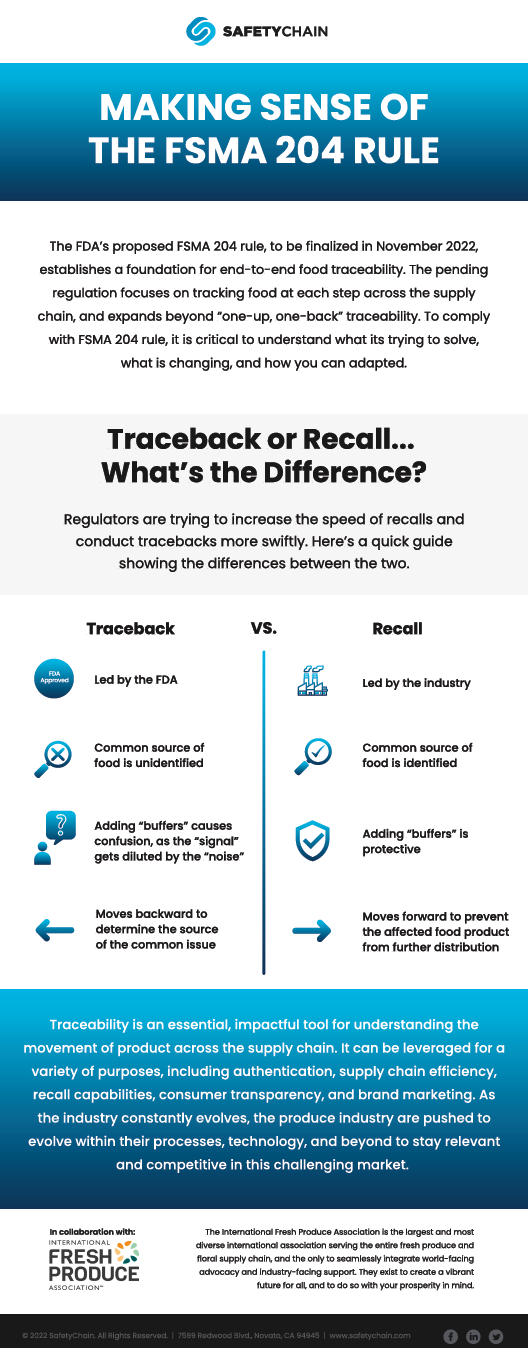

In September 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released a 199-page Proposed Rule for Record Keeping for Food Traceability as part of the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA).

The FDA has since solicited industry comments on the proposed rule (aka FSMA 204), which is scheduled to be finalized and submitted to the Federal Register by Nov. 7, 2022. Once it goes into effect on Jan. 6, 2025, FSMA 204 will apply to all foods on the FDA’s Food Traceability List (FTL). That includes all fresh-cut fruits and vegetables, as well as ready-to-eat deli salads, fresh cucumbers, leafy greens, melons, peppers, tomatoes, tropical tree fruits and sprouts.

The proposed rule goes beyond the traceability data requirements outlined in the Produce Traceability Initiative (PTI), an 11-year-old industry-led initiative that now applies to 65% of all cases of fresh produce in the U.S.

On Oct. 14, 2021, the Produce Marketing Association (PMA), one of the leaders of PTI, presented a webinar featuring three prominent food traceability platform experts to weigh in on how the proposed rule could affect the produce industry and what is being done to get ready for it.

The webinar featured:

On Oct. 14, 2021, the Produce Marketing Association (PMA), one of the leaders of PTI, presented a webinar featuring three prominent food traceability platform experts to weigh in on how the proposed rule could affect the produce industry and what is being done to get ready for it.

The webinar featured:

Tracey: Do you know if foodservice and/or retailers are going to have a separate set of requirements for the FTL and another set for products not on that list?

Anderson: It isn’t about the specifics yet, but it is about the process. We have all of these foodservice distributors and retailers that know they’re going tohavetodothis—andthisisa data problem. We’ve got 65% PTI coverage, which is awesome, but it doesn’t help me create an electronic record that I can share with the FDA. Either they have to figure out how to convert physical labels to a digital record, which no one wants to do, or they need to get ahead of how they capture that data in the first place. That’s really where we are focusing with our customers now. They’re not planning to have a separate (set of rules) on the FTL or not, but they are starting with the foods that are on the list. People may already be getting contacted by some of these big distributors to let them know they’re going to be collecting this data, so they need to start providing the data to them. The key is they’re starting now. If people wait until 2022, when the rule is finalized to start doing this, good luck being ready by 2025.

Athanassiadis: We’re expecting that our customers are going to treat all fresh produce items consistently. The produce listed on the FTL list make up almost 40% of total produce, so it doesn’t make sense for receivers to have two different requirements depending. … If you look at how other industries digitally track the movement of planes, ride sharing or packaged goods, it’s clear that we must study how these technologies can improve tracking when it comes to food.

Treacy: There needs to be one method — not just for produce — but for all perishables because their employees don’t just receive produce.

Treacy: Does your system currently capture all the critical tracking events (CTEs) — growering, receiving, creating, transformation and shipping — required in FSMA?

Baggett: We capture all five of the critical tracking events. One thing I want to point out is that RedLine is a little different than our other two speakers in that we really focus on the grower side. We work with the retailers in passing the data through the blockchain or ASN or whatever format they want, but our focus is really on the growing side.

Treacy: How are you approaching the input number data requirement?

Anderson: Historically, (the input number) hasn’t been a data requirement, but that’s an example of where we have broadened our reach to help with that entire importing process. A couple of examples: on the grower side, is being able to help them clear customs faster, being adding extra elements under our traceability solution. On the buyer side, for the large retailers, we now have direct integrations to their customs brokers and their importers that we

can bring that data in.

Athanassiadis: The import number is just one more data field, which our system is very capable of handling. We already have several customers that have asked us to include additional data fields in their traceability records over and above to the industry-wide harmonized labels. (Additional data fields) don’t need to be on the label itself as long as it’s in the database, it can be shared with any of their customers in the supply chain.

Treacy: I bet none of you are capturing the person who assigned the lot number. (laughs)

Tracey: Do you know if foodservice and/or retailers are going to have a separate set of requirements for the FTL and another set for products not on that list?

Anderson: It isn’t about the specifics yet, but it is about the process. We have all of these foodservice distributors and retailers that know they’re going tohavetodothis—andthisisa data problem. We’ve got 65% PTI coverage, which is awesome, but it doesn’t help me create an electronic record that I can share with the FDA. Either they have to figure out how to convert physical labels to a digital record, which no one wants to do, or they need to get ahead of how they capture that data in the first place. That’s really where we are focusing with our customers now. They’re not planning to have a separate (set of rules) on the FTL or not, but they are starting with the foods that are on the list. People may already be getting contacted by some of these big distributors to let them know they’re going to be collecting this data, so they need to start providing the data to them. The key is they’re starting now. If people wait until 2022, when the rule is finalized to start doing this, good luck being ready by 2025.

Athanassiadis: We’re expecting that our customers are going to treat all fresh produce items consistently. The produce listed on the FTL list make up almost 40% of total produce, so it doesn’t make sense for receivers to have two different requirements depending. … If you look at how other industries digitally track the movement of planes, ride sharing or packaged goods, it’s clear that we must study how these technologies can improve tracking when it comes to food.

Treacy: There needs to be one method — not just for produce — but for all perishables because their employees don’t just receive produce.

Treacy: Does your system currently capture all the critical tracking events (CTEs) — growering, receiving, creating, transformation and shipping — required in FSMA?

Baggett: We capture all five of the critical tracking events. One thing I want to point out is that RedLine is a little different than our other two speakers in that we really focus on the grower side. We work with the retailers in passing the data through the blockchain or ASN or whatever format they want, but our focus is really on the growing side.

Treacy: How are you approaching the input number data requirement?

Anderson: Historically, (the input number) hasn’t been a data requirement, but that’s an example of where we have broadened our reach to help with that entire importing process. A couple of examples: on the grower side, is being able to help them clear customs faster, being adding extra elements under our traceability solution. On the buyer side, for the large retailers, we now have direct integrations to their customs brokers and their importers that we

can bring that data in.

Athanassiadis: The import number is just one more data field, which our system is very capable of handling. We already have several customers that have asked us to include additional data fields in their traceability records over and above to the industry-wide harmonized labels. (Additional data fields) don’t need to be on the label itself as long as it’s in the database, it can be shared with any of their customers in the supply chain.

Treacy: I bet none of you are capturing the person who assigned the lot number. (laughs)

Athanassiadis: I hate to disappoint you, Ed, (laughs) but we are already doing that. Like I’ve said, it’s not something that’s on the PTI label or the bill of lading, but it’s metadata. It’s a standard attribute that’s stored in the cloud, along with the G10, the lot and any other requests that happen to come along. Whenever someone touches the product, we record that and make it available as required.

Anderson: (We’re handling that) the same. We capture the signer, but also the creator of the lot if we need to talk about the geocoding or the actual logic behind what that lotting means. To me, the more interesting question is about the sharing piece of it. From a data privacy standpoint, I don’t want to put somebody’s name, phone number and email address on a PTI label. So, what we’re intending to do there is capture that data and make it available through a masked ID number. … We’ve been capturing that data for years, but no one has asked for it. Is it relevant? Maybe for internal process control or to run analysis on workloads or something like that, I could maybe see some value there. But in terms of traceability, I don’t know what the value is from that data.

Baggett: We do capture that, too. We capture who does each transaction, whether it’s a receipt, assignment of a lot number, a shipment, a movement, etc. This (rule proposal is) something I also found confusing. It seems to be based on the premise — the bulk product that came in — didn’t already have a lot number. If you follow the grower side of things, when you do the planting, you assign a lot number right then. It’s not like that is something that’s unique to the receiving or the harvest-process end of things. It’s something that’s created before it’s used in the grower records to figure out the cost — how much water was added or fertilizer was applied or any type of nutrients, etc. This is one area I am hoping will be omitted in the final rule, because I just don’t see it as relevant.

Treacy: The other issue I have with those three data elements is that there is no way for the receiver to be able to validate the truth of the information they’re being given. With a lot number or G10, it’s right on the label.

Athanassiadis: I hate to disappoint you, Ed, (laughs) but we are already doing that. Like I’ve said, it’s not something that’s on the PTI label or the bill of lading, but it’s metadata. It’s a standard attribute that’s stored in the cloud, along with the G10, the lot and any other requests that happen to come along. Whenever someone touches the product, we record that and make it available as required.

Anderson: (We’re handling that) the same. We capture the signer, but also the creator of the lot if we need to talk about the geocoding or the actual logic behind what that lotting means. To me, the more interesting question is about the sharing piece of it. From a data privacy standpoint, I don’t want to put somebody’s name, phone number and email address on a PTI label. So, what we’re intending to do there is capture that data and make it available through a masked ID number. … We’ve been capturing that data for years, but no one has asked for it. Is it relevant? Maybe for internal process control or to run analysis on workloads or something like that, I could maybe see some value there. But in terms of traceability, I don’t know what the value is from that data.

Baggett: We do capture that, too. We capture who does each transaction, whether it’s a receipt, assignment of a lot number, a shipment, a movement, etc. This (rule proposal is) something I also found confusing. It seems to be based on the premise — the bulk product that came in — didn’t already have a lot number. If you follow the grower side of things, when you do the planting, you assign a lot number right then. It’s not like that is something that’s unique to the receiving or the harvest-process end of things. It’s something that’s created before it’s used in the grower records to figure out the cost — how much water was added or fertilizer was applied or any type of nutrients, etc. This is one area I am hoping will be omitted in the final rule, because I just don’t see it as relevant.

Treacy: The other issue I have with those three data elements is that there is no way for the receiver to be able to validate the truth of the information they’re being given. With a lot number or G10, it’s right on the label.

Treacy: How are your foodservice or retail customers planning to capture the lot number at the store or restaurant?

Anderson: With great trepidation (laughs). From a broader perspective, two or three years ago, if you tried to have a conversation with a foodservice or retailer about store-level traceability, they would have said, ‘We’ve assessed it, it’s too expensive. We’re not even going to talk about it.’ At the same time, there were a lot of other problems they were trying to solve that were pretty directly related to having better processes in place for allocating product to stores. What I mean by that is we’ve had customers tell us that ‘our fresh problem is really an inventory problem, because we don’t have good visibility into expiration dates, harvest dates and how long something is going to be good for, so we’re not making the optimal decision on what to move to stores. I am a believer that this problem — and I won’t say 100% solved — but it is a problem of allocation and that’s based on accurate data coming into the retailer or foodservice restaurant on product coming in and where to slot it.

Athanassiadis: There are two basic ways we’re working with our customers on this. We are working with our retail customers to track lot-level detail out of their DCs and into their stores using our Insights Quality platform without requiring additional IT investment at their end. We have thousands of loads of products going into our various customers’ distribution centers. We then use our system to evaluate the quality of the product they’re receiving. That’s the first step in order for them to know what product is coming, track through the DC and then onto the store. Alternatively, and perhaps more applicable to those companies that don’t use our platform, we’re working with them to familiarize on how to use the voicepin code — the four digits on the lower right of the harmonized PTI label — as an alternative means for lot-level tracking to an individual store without having to scan cases. … Inventory pickers can use these four digits, well, actually probably just the first two digits, to quickly ensure they’re picking the correct produce, therefore, enabling the inventory management system to continue to track lot-level detail for traceability and advanced inventory rotation. … We, as software companies, need to work with our customers to help them realize the full value of the tools that they have.

Baggett: We’ve been working with the PTI leadership team for a long time. What we’ve seen from the growth side is that they have the information, they’re recording it, they’re preparing to do it. It’s been at the retail side where we’ve had the breakdowns. Some of the work we’ve done has shown that some of the retailers are still using POs and other means of tracking, when the G10 has been out there now for 10 years. While some of them are slow to get there, I don’t want to dismiss that they’ve had the time to get there. Now they have a date they have to hit. Now they’re going to get serious about it because the FDA is going to be coming down on them. In some of the romaine recalls, they didn’t do it as a recall but an advisory, so that shifted who paid for it. I think that woke up the retailers.

Audience question: How long will it take until we’re all speaking the same language and using the same format on (the data that needs to be shared)? Todd, do you think PTI will develop a standard for those data elements in this?

Baggett: Given that the FDA has said they’re not going to give us the very specifics, we’ve already done some of that in a technology working group. We did an experiment where we tried a traceability Excel spreadsheet looking at that as the easiest level that all sizes of growers could accomplish. I think the good news is that we will be able to comply with this and we will be able to get the data elements. It will be something, as an industry, we need to agree upon. One thing we heard from the FDA loud and clear is when they get the data in multiple formats, the processing time goes up. When there is food that is potentially harmful, we need to get that out of the market as quickly as possible. Equally as important is that we have that level of specificity so that we’re not recalling a whole commodity of product, that we’re to the point where we can say, it’s one, two, three or four of these lots that came from one or two of these growers. Otherwise, the burden on these growers is just too big. We’ve seen the stats that the average recall costs $10 million.

Treacy: How are your foodservice or retail customers planning to capture the lot number at the store or restaurant?

Anderson: With great trepidation (laughs). From a broader perspective, two or three years ago, if you tried to have a conversation with a foodservice or retailer about store-level traceability, they would have said, ‘We’ve assessed it, it’s too expensive. We’re not even going to talk about it.’ At the same time, there were a lot of other problems they were trying to solve that were pretty directly related to having better processes in place for allocating product to stores. What I mean by that is we’ve had customers tell us that ‘our fresh problem is really an inventory problem, because we don’t have good visibility into expiration dates, harvest dates and how long something is going to be good for, so we’re not making the optimal decision on what to move to stores. I am a believer that this problem — and I won’t say 100% solved — but it is a problem of allocation and that’s based on accurate data coming into the retailer or foodservice restaurant on product coming in and where to slot it.

Athanassiadis: There are two basic ways we’re working with our customers on this. We are working with our retail customers to track lot-level detail out of their DCs and into their stores using our Insights Quality platform without requiring additional IT investment at their end. We have thousands of loads of products going into our various customers’ distribution centers. We then use our system to evaluate the quality of the product they’re receiving. That’s the first step in order for them to know what product is coming, track through the DC and then onto the store. Alternatively, and perhaps more applicable to those companies that don’t use our platform, we’re working with them to familiarize on how to use the voicepin code — the four digits on the lower right of the harmonized PTI label — as an alternative means for lot-level tracking to an individual store without having to scan cases. … Inventory pickers can use these four digits, well, actually probably just the first two digits, to quickly ensure they’re picking the correct produce, therefore, enabling the inventory management system to continue to track lot-level detail for traceability and advanced inventory rotation. … We, as software companies, need to work with our customers to help them realize the full value of the tools that they have.

Baggett: We’ve been working with the PTI leadership team for a long time. What we’ve seen from the growth side is that they have the information, they’re recording it, they’re preparing to do it. It’s been at the retail side where we’ve had the breakdowns. Some of the work we’ve done has shown that some of the retailers are still using POs and other means of tracking, when the G10 has been out there now for 10 years. While some of them are slow to get there, I don’t want to dismiss that they’ve had the time to get there. Now they have a date they have to hit. Now they’re going to get serious about it because the FDA is going to be coming down on them. In some of the romaine recalls, they didn’t do it as a recall but an advisory, so that shifted who paid for it. I think that woke up the retailers.

Audience question: How long will it take until we’re all speaking the same language and using the same format on (the data that needs to be shared)? Todd, do you think PTI will develop a standard for those data elements in this?

Baggett: Given that the FDA has said they’re not going to give us the very specifics, we’ve already done some of that in a technology working group. We did an experiment where we tried a traceability Excel spreadsheet looking at that as the easiest level that all sizes of growers could accomplish. I think the good news is that we will be able to comply with this and we will be able to get the data elements. It will be something, as an industry, we need to agree upon. One thing we heard from the FDA loud and clear is when they get the data in multiple formats, the processing time goes up. When there is food that is potentially harmful, we need to get that out of the market as quickly as possible. Equally as important is that we have that level of specificity so that we’re not recalling a whole commodity of product, that we’re to the point where we can say, it’s one, two, three or four of these lots that came from one or two of these growers. Otherwise, the burden on these growers is just too big. We’ve seen the stats that the average recall costs $10 million.

Click to enlarge. Find out more at safetychain.com.

- Moderator: Ed Treacy, PMA’s VP of Supply Chain and Sustainability

- Mike Anderson, iTradeNetwork, VP of Solution Consulting

- Minos Athanassiadis, iFoodDS, VP (formerly of Dole Fresh, Underwood Ranches)

- Todd Baggett, RedLine Solutions, president and CEO Here are some highlights from the hour-long webinar:

Tracey: Do you know if foodservice and/or retailers are going to have a separate set of requirements for the FTL and another set for products not on that list?

Anderson: It isn’t about the specifics yet, but it is about the process. We have all of these foodservice distributors and retailers that know they’re going tohavetodothis—andthisisa data problem. We’ve got 65% PTI coverage, which is awesome, but it doesn’t help me create an electronic record that I can share with the FDA. Either they have to figure out how to convert physical labels to a digital record, which no one wants to do, or they need to get ahead of how they capture that data in the first place. That’s really where we are focusing with our customers now. They’re not planning to have a separate (set of rules) on the FTL or not, but they are starting with the foods that are on the list. People may already be getting contacted by some of these big distributors to let them know they’re going to be collecting this data, so they need to start providing the data to them. The key is they’re starting now. If people wait until 2022, when the rule is finalized to start doing this, good luck being ready by 2025.

Athanassiadis: We’re expecting that our customers are going to treat all fresh produce items consistently. The produce listed on the FTL list make up almost 40% of total produce, so it doesn’t make sense for receivers to have two different requirements depending. … If you look at how other industries digitally track the movement of planes, ride sharing or packaged goods, it’s clear that we must study how these technologies can improve tracking when it comes to food.

Treacy: There needs to be one method — not just for produce — but for all perishables because their employees don’t just receive produce.

Treacy: Does your system currently capture all the critical tracking events (CTEs) — growering, receiving, creating, transformation and shipping — required in FSMA?

Baggett: We capture all five of the critical tracking events. One thing I want to point out is that RedLine is a little different than our other two speakers in that we really focus on the grower side. We work with the retailers in passing the data through the blockchain or ASN or whatever format they want, but our focus is really on the growing side.

Treacy: How are you approaching the input number data requirement?

Anderson: Historically, (the input number) hasn’t been a data requirement, but that’s an example of where we have broadened our reach to help with that entire importing process. A couple of examples: on the grower side, is being able to help them clear customs faster, being adding extra elements under our traceability solution. On the buyer side, for the large retailers, we now have direct integrations to their customs brokers and their importers that we

can bring that data in.

Athanassiadis: The import number is just one more data field, which our system is very capable of handling. We already have several customers that have asked us to include additional data fields in their traceability records over and above to the industry-wide harmonized labels. (Additional data fields) don’t need to be on the label itself as long as it’s in the database, it can be shared with any of their customers in the supply chain.

Treacy: I bet none of you are capturing the person who assigned the lot number. (laughs)

Tracey: Do you know if foodservice and/or retailers are going to have a separate set of requirements for the FTL and another set for products not on that list?

Anderson: It isn’t about the specifics yet, but it is about the process. We have all of these foodservice distributors and retailers that know they’re going tohavetodothis—andthisisa data problem. We’ve got 65% PTI coverage, which is awesome, but it doesn’t help me create an electronic record that I can share with the FDA. Either they have to figure out how to convert physical labels to a digital record, which no one wants to do, or they need to get ahead of how they capture that data in the first place. That’s really where we are focusing with our customers now. They’re not planning to have a separate (set of rules) on the FTL or not, but they are starting with the foods that are on the list. People may already be getting contacted by some of these big distributors to let them know they’re going to be collecting this data, so they need to start providing the data to them. The key is they’re starting now. If people wait until 2022, when the rule is finalized to start doing this, good luck being ready by 2025.

Athanassiadis: We’re expecting that our customers are going to treat all fresh produce items consistently. The produce listed on the FTL list make up almost 40% of total produce, so it doesn’t make sense for receivers to have two different requirements depending. … If you look at how other industries digitally track the movement of planes, ride sharing or packaged goods, it’s clear that we must study how these technologies can improve tracking when it comes to food.

Treacy: There needs to be one method — not just for produce — but for all perishables because their employees don’t just receive produce.

Treacy: Does your system currently capture all the critical tracking events (CTEs) — growering, receiving, creating, transformation and shipping — required in FSMA?

Baggett: We capture all five of the critical tracking events. One thing I want to point out is that RedLine is a little different than our other two speakers in that we really focus on the grower side. We work with the retailers in passing the data through the blockchain or ASN or whatever format they want, but our focus is really on the growing side.

Treacy: How are you approaching the input number data requirement?

Anderson: Historically, (the input number) hasn’t been a data requirement, but that’s an example of where we have broadened our reach to help with that entire importing process. A couple of examples: on the grower side, is being able to help them clear customs faster, being adding extra elements under our traceability solution. On the buyer side, for the large retailers, we now have direct integrations to their customs brokers and their importers that we

can bring that data in.

Athanassiadis: The import number is just one more data field, which our system is very capable of handling. We already have several customers that have asked us to include additional data fields in their traceability records over and above to the industry-wide harmonized labels. (Additional data fields) don’t need to be on the label itself as long as it’s in the database, it can be shared with any of their customers in the supply chain.

Treacy: I bet none of you are capturing the person who assigned the lot number. (laughs)

Athanassiadis: I hate to disappoint you, Ed, (laughs) but we are already doing that. Like I’ve said, it’s not something that’s on the PTI label or the bill of lading, but it’s metadata. It’s a standard attribute that’s stored in the cloud, along with the G10, the lot and any other requests that happen to come along. Whenever someone touches the product, we record that and make it available as required.

Anderson: (We’re handling that) the same. We capture the signer, but also the creator of the lot if we need to talk about the geocoding or the actual logic behind what that lotting means. To me, the more interesting question is about the sharing piece of it. From a data privacy standpoint, I don’t want to put somebody’s name, phone number and email address on a PTI label. So, what we’re intending to do there is capture that data and make it available through a masked ID number. … We’ve been capturing that data for years, but no one has asked for it. Is it relevant? Maybe for internal process control or to run analysis on workloads or something like that, I could maybe see some value there. But in terms of traceability, I don’t know what the value is from that data.

Baggett: We do capture that, too. We capture who does each transaction, whether it’s a receipt, assignment of a lot number, a shipment, a movement, etc. This (rule proposal is) something I also found confusing. It seems to be based on the premise — the bulk product that came in — didn’t already have a lot number. If you follow the grower side of things, when you do the planting, you assign a lot number right then. It’s not like that is something that’s unique to the receiving or the harvest-process end of things. It’s something that’s created before it’s used in the grower records to figure out the cost — how much water was added or fertilizer was applied or any type of nutrients, etc. This is one area I am hoping will be omitted in the final rule, because I just don’t see it as relevant.

Treacy: The other issue I have with those three data elements is that there is no way for the receiver to be able to validate the truth of the information they’re being given. With a lot number or G10, it’s right on the label.

Athanassiadis: I hate to disappoint you, Ed, (laughs) but we are already doing that. Like I’ve said, it’s not something that’s on the PTI label or the bill of lading, but it’s metadata. It’s a standard attribute that’s stored in the cloud, along with the G10, the lot and any other requests that happen to come along. Whenever someone touches the product, we record that and make it available as required.

Anderson: (We’re handling that) the same. We capture the signer, but also the creator of the lot if we need to talk about the geocoding or the actual logic behind what that lotting means. To me, the more interesting question is about the sharing piece of it. From a data privacy standpoint, I don’t want to put somebody’s name, phone number and email address on a PTI label. So, what we’re intending to do there is capture that data and make it available through a masked ID number. … We’ve been capturing that data for years, but no one has asked for it. Is it relevant? Maybe for internal process control or to run analysis on workloads or something like that, I could maybe see some value there. But in terms of traceability, I don’t know what the value is from that data.

Baggett: We do capture that, too. We capture who does each transaction, whether it’s a receipt, assignment of a lot number, a shipment, a movement, etc. This (rule proposal is) something I also found confusing. It seems to be based on the premise — the bulk product that came in — didn’t already have a lot number. If you follow the grower side of things, when you do the planting, you assign a lot number right then. It’s not like that is something that’s unique to the receiving or the harvest-process end of things. It’s something that’s created before it’s used in the grower records to figure out the cost — how much water was added or fertilizer was applied or any type of nutrients, etc. This is one area I am hoping will be omitted in the final rule, because I just don’t see it as relevant.

Treacy: The other issue I have with those three data elements is that there is no way for the receiver to be able to validate the truth of the information they’re being given. With a lot number or G10, it’s right on the label.

Treacy: How are your foodservice or retail customers planning to capture the lot number at the store or restaurant?

Anderson: With great trepidation (laughs). From a broader perspective, two or three years ago, if you tried to have a conversation with a foodservice or retailer about store-level traceability, they would have said, ‘We’ve assessed it, it’s too expensive. We’re not even going to talk about it.’ At the same time, there were a lot of other problems they were trying to solve that were pretty directly related to having better processes in place for allocating product to stores. What I mean by that is we’ve had customers tell us that ‘our fresh problem is really an inventory problem, because we don’t have good visibility into expiration dates, harvest dates and how long something is going to be good for, so we’re not making the optimal decision on what to move to stores. I am a believer that this problem — and I won’t say 100% solved — but it is a problem of allocation and that’s based on accurate data coming into the retailer or foodservice restaurant on product coming in and where to slot it.

Athanassiadis: There are two basic ways we’re working with our customers on this. We are working with our retail customers to track lot-level detail out of their DCs and into their stores using our Insights Quality platform without requiring additional IT investment at their end. We have thousands of loads of products going into our various customers’ distribution centers. We then use our system to evaluate the quality of the product they’re receiving. That’s the first step in order for them to know what product is coming, track through the DC and then onto the store. Alternatively, and perhaps more applicable to those companies that don’t use our platform, we’re working with them to familiarize on how to use the voicepin code — the four digits on the lower right of the harmonized PTI label — as an alternative means for lot-level tracking to an individual store without having to scan cases. … Inventory pickers can use these four digits, well, actually probably just the first two digits, to quickly ensure they’re picking the correct produce, therefore, enabling the inventory management system to continue to track lot-level detail for traceability and advanced inventory rotation. … We, as software companies, need to work with our customers to help them realize the full value of the tools that they have.

Baggett: We’ve been working with the PTI leadership team for a long time. What we’ve seen from the growth side is that they have the information, they’re recording it, they’re preparing to do it. It’s been at the retail side where we’ve had the breakdowns. Some of the work we’ve done has shown that some of the retailers are still using POs and other means of tracking, when the G10 has been out there now for 10 years. While some of them are slow to get there, I don’t want to dismiss that they’ve had the time to get there. Now they have a date they have to hit. Now they’re going to get serious about it because the FDA is going to be coming down on them. In some of the romaine recalls, they didn’t do it as a recall but an advisory, so that shifted who paid for it. I think that woke up the retailers.

Audience question: How long will it take until we’re all speaking the same language and using the same format on (the data that needs to be shared)? Todd, do you think PTI will develop a standard for those data elements in this?

Baggett: Given that the FDA has said they’re not going to give us the very specifics, we’ve already done some of that in a technology working group. We did an experiment where we tried a traceability Excel spreadsheet looking at that as the easiest level that all sizes of growers could accomplish. I think the good news is that we will be able to comply with this and we will be able to get the data elements. It will be something, as an industry, we need to agree upon. One thing we heard from the FDA loud and clear is when they get the data in multiple formats, the processing time goes up. When there is food that is potentially harmful, we need to get that out of the market as quickly as possible. Equally as important is that we have that level of specificity so that we’re not recalling a whole commodity of product, that we’re to the point where we can say, it’s one, two, three or four of these lots that came from one or two of these growers. Otherwise, the burden on these growers is just too big. We’ve seen the stats that the average recall costs $10 million.

Treacy: How are your foodservice or retail customers planning to capture the lot number at the store or restaurant?

Anderson: With great trepidation (laughs). From a broader perspective, two or three years ago, if you tried to have a conversation with a foodservice or retailer about store-level traceability, they would have said, ‘We’ve assessed it, it’s too expensive. We’re not even going to talk about it.’ At the same time, there were a lot of other problems they were trying to solve that were pretty directly related to having better processes in place for allocating product to stores. What I mean by that is we’ve had customers tell us that ‘our fresh problem is really an inventory problem, because we don’t have good visibility into expiration dates, harvest dates and how long something is going to be good for, so we’re not making the optimal decision on what to move to stores. I am a believer that this problem — and I won’t say 100% solved — but it is a problem of allocation and that’s based on accurate data coming into the retailer or foodservice restaurant on product coming in and where to slot it.

Athanassiadis: There are two basic ways we’re working with our customers on this. We are working with our retail customers to track lot-level detail out of their DCs and into their stores using our Insights Quality platform without requiring additional IT investment at their end. We have thousands of loads of products going into our various customers’ distribution centers. We then use our system to evaluate the quality of the product they’re receiving. That’s the first step in order for them to know what product is coming, track through the DC and then onto the store. Alternatively, and perhaps more applicable to those companies that don’t use our platform, we’re working with them to familiarize on how to use the voicepin code — the four digits on the lower right of the harmonized PTI label — as an alternative means for lot-level tracking to an individual store without having to scan cases. … Inventory pickers can use these four digits, well, actually probably just the first two digits, to quickly ensure they’re picking the correct produce, therefore, enabling the inventory management system to continue to track lot-level detail for traceability and advanced inventory rotation. … We, as software companies, need to work with our customers to help them realize the full value of the tools that they have.

Baggett: We’ve been working with the PTI leadership team for a long time. What we’ve seen from the growth side is that they have the information, they’re recording it, they’re preparing to do it. It’s been at the retail side where we’ve had the breakdowns. Some of the work we’ve done has shown that some of the retailers are still using POs and other means of tracking, when the G10 has been out there now for 10 years. While some of them are slow to get there, I don’t want to dismiss that they’ve had the time to get there. Now they have a date they have to hit. Now they’re going to get serious about it because the FDA is going to be coming down on them. In some of the romaine recalls, they didn’t do it as a recall but an advisory, so that shifted who paid for it. I think that woke up the retailers.

Audience question: How long will it take until we’re all speaking the same language and using the same format on (the data that needs to be shared)? Todd, do you think PTI will develop a standard for those data elements in this?

Baggett: Given that the FDA has said they’re not going to give us the very specifics, we’ve already done some of that in a technology working group. We did an experiment where we tried a traceability Excel spreadsheet looking at that as the easiest level that all sizes of growers could accomplish. I think the good news is that we will be able to comply with this and we will be able to get the data elements. It will be something, as an industry, we need to agree upon. One thing we heard from the FDA loud and clear is when they get the data in multiple formats, the processing time goes up. When there is food that is potentially harmful, we need to get that out of the market as quickly as possible. Equally as important is that we have that level of specificity so that we’re not recalling a whole commodity of product, that we’re to the point where we can say, it’s one, two, three or four of these lots that came from one or two of these growers. Otherwise, the burden on these growers is just too big. We’ve seen the stats that the average recall costs $10 million.